20 Sep 2024

How is Action 22 tackling the climate crisis?

Restricting the most polluting vehicles is essential to meeting climate targets and World Health Organization (WHO) air pollution standards. Poor air quality is the biggest environmental threat to public health in the UK.

Southampton’s Local NO2 Plan has used a range of measures to lower emissions of nitrogen dioxide (the pollutant of greatest concern in the city) and boost health, without charging drivers to use the city’s roads. The city has above-average rates of preventable respiratory and cardiovascular early death.

Southampton City Council was one of the first 5 local authorities required by the government to assess the need for a charging Clean Air Zone (CAZ), to achieve compliance with Air Quality Limits in the shortest possible time. While it was found that a charging CAZ wasn't necessary, the council committed to implementing a series of non-charging measures to help ensure compliance could be maintained, and to deliver ongoing improvements to air quality and public health.

The Local NO2 Plan aims to achieve largely what a charging CAZ aims to, without some of the unintended consequences charging may have.

Since 2015, over 60 local authorities in areas of non-compliance have collaborated with central government to agree on plans to deliver compliance.

Feedback from stakeholders led the council to launch its Local NO2 Plan. It includes:

- The Clean Bus Retrofit Scheme, retrofitting 145 of the city’s licensed buses with emission reduction technology, bringing them in line with the best diesel emission standards and effectively achieving a CAZ-compliant bus fleet.

- Ensuring city buses and newly licensed taxis meet the cleanest standard of diesel.

- Creating a low-emission taxi incentive scheme, offering drivers up to £3,000 towards switching their vehicle to an electric or low-emission model, while also installing 2 taxi-only rapid charging points, which will be free to use until autumn 2023.

- Enhancing the use of a sustainable distribution centre that lowers the number of heavy goods vehicles entering the city centre, by combining loads from partially empty lorries in fewer but fuller vehicles.

- Concessions for private car owners with electric vehicles and offering free access to 50 chargers until the end of 2022. For example, electric car drivers were exempt from the Itchen Bridge toll fee and can also receive a 90% discount on a city centre seasonal parking ticket.

- Working with local businesses to develop delivery and service plans that reduce emissions through greener last-mile delivery alternatives, such as electric vans and electric cargo bikes.

The council submitted a business case to the government in January 2019, and the Plan was approved for implementation in February 2019. Since then, the council has delivered the Plan as required by the government. The Plan concluded at the end of 2021.

Building on the progress made by the NO2 Plan, Southampton will continue its clean air work under its new Air Quality Action Plan for 2023-2028. The plan includes 60 actions to further clean up the city’s air, including:

- 3 behavioural change engagement projects around woodburning, in schools and in healthcare, forming an overarching air quality behaviour change programme.

- A network of high-tech air quality monitors across the city providing real-time air quality forecasts.

- Enhanced air quality requirements in the planning process.

- A “try before you buy” scheme for electric taxis and light commercial vehicles, with 8 new rapid chargepoints to be installed to support uptake.

- Identifying opportunities for Active Travel Zones.

- Supporting micromobility with rental manual bikes, e-bikes and cargo bikes.

In addition, the council has produced a Green City Charter, partially informed by a public consultation on the CAZ in 2018. The Charter introduced a framework of targets and commitments for city stakeholders (including the council) to aspire to, attracted over 100 signatories and was the basis for the council’s subsequent Green City Plan.

The Green City Plan includes further commitments to cut carbon and improve air quality, including:

- Infrastructure to support a zero-emission public transport system by 2030.

- 2 Active Travel Zones by 2025.

- 15% of journeys into the city by bike by 2027.

What impact has the project had?

Impact on air pollution

Electric or low-emission vehicles now make up the majority of the city taxi fleet. Until recently, the fleet was almost entirely made up of vehicles meeting the more polluting Euro 3 or Euro 4 standard. Now 62% of fleet vehicles are hybrids, 1% are electric, and 37% are new Euro 4 petrol or Euro 6 diesel vehicles, meaning the fleet is essentially CAZ-compliant. Most buses in Southampton also meet the Euro 6 standard, and all must comply with this standard by spring 2024 (see more in the "Lessons from Southampton" section below).

Average emissions for taxis and private hire vehicles in the local authority’s fleet decreased from 0.144 g/km to less than 0.06 g/km of NOx between 2019 and 2023.

Annual average concentrations of NO2 declined by approximately 14% between 2012 and 2019 in key areas. Much of this was driven by national improvements, but also the work Southampton City Council carried out to fast-track improvements. Further decreases were monitored in 2020, but these are attributable to the pandemic.

In a post-pandemic world, it remains difficult to attribute any improvements in air quality from 2020 onwards to specific action by councils. However, data for 2022 shows that NO2 levels at all sites in Southampton are lower than in 2019 and, although levels at most sites are going up slightly compared to 2020, they're broadly similar to 2021 despite there being no lockdowns in response to COVID-19. This is likely due to established flexible and home-working arrangements, which have helped flatten peak-time congestion. Due to these continued lower levels, the council remains compliant with all national air quality objectives, which it first achieved in 2020.

Impact on carbon emissions

While the Local NO2 Plan is principally a measure to tackle poor air quality, there are clear benefits to the decarbonisation agenda. This project is cutting carbon, tackling Southampton’s poor air quality and improving local people’s health. All while avoiding the direct fees for drivers brought in by many CAZ. For example, the switch to clean taxis is saving an estimated 1.7 tonnes of carbon every year, while also providing a cleaner, quieter and more modern fleet that benefits both customers and drivers.

Measures in the council’s new Air Quality Action Plan have been selected partly on their potential to deliver co-benefits for carbon reduction, as well as other priorities including health and wellbeing and noise reduction. The Plan also avoids measures where outcomes might conflict with other priority areas.

Health benefits

According to Public Health England, 5.9% of annual deaths in Southampton can be attributed to air pollution, which is higher than the regional figure for Southeast England. Yet analysis by the Clean Air Fund shows that if air pollution is cut by a fifth, Southampton could see a raft of health benefits, especially for children. 150 fewer children would suffer from reduced lung function, 81 fewer would suffer from chest infections, and 69 fewer would suffer from symptoms related to bronchitis. Furthermore, cleaner air could see a 4.2% decrease in the risk of coronary heart disease and a 5.9% decrease in lung cancer cases.

Because health is intertwined with socio-economic status, clean air can also be a way of tackling inequality. For instance, in the most deprived areas of Southampton, emergency admissions for asthma are 1.92 times higher than in its least deprived neighbourhoods.

The new Air Quality Action Plan aims to bring about a continual improvement in air quality in the city and continue to reduce the impact pollution has on the health of residents. For this reason, measures targeting particulate matter have been committed to, namely those in the engagement programme consisting of behaviour change projects around woodburning, healthcare and schools.

Award-winning

In June 2023 Southampton City Council was awarded the Best Air Quality Strategy award at the public sector Fleet International Awards, for the roll-out of its state-of-the-art air quality monitoring and modelling network supporting its behaviour change programme.

What made this work?

Political commitment

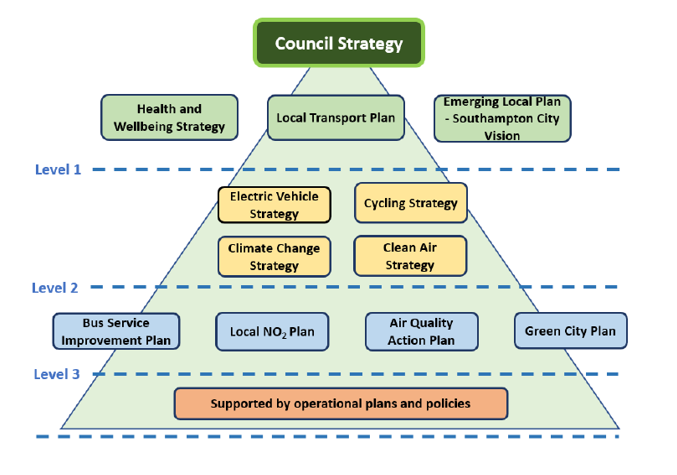

Prior to the launch of the NO2 plan, Southampton City Council had already reported on the business case for improving air quality and achieving EU NO2 compliance in the shortest possible time. On top of this, the local authority has developed a clean air strategy for 2019 to 2025, making it clear that air quality is a significant priority and demonstrating the political will required to see these measures through.

Public backing

In 2018, a public consultation was marketed and promoted to local people on air pollution in Southampton to ensure the council understood the views of as many communities and other stakeholders as possible. The majority of respondents (75%) said that air quality was a fairly or very big problem. Stakeholders suggested support for active travel, increases in lower-emission vehicles, and promoting and improving public transport as popular measures to partly tackle this issue. This gave the council a mandate to press on with the Local NO2 Plan and encourage low-emission vehicles, along with other air quality measures.

In addition, the public backing for action on wider issues led to the creation of the Green City Plan, a wider council-driven programme including climate change, ecology and waste. As part of its Green City Plan, the council is aiming to deliver a zero-emission public transport system across the city and increase the number of journeys by bike.

Community engagement

The council’s public consultation on the original proposal for a charging CAZ received over 9,000 responses.

The consultation showed support for the impact the NO2 Plan would have, but also highlighted that local residents wanted the council to be bolder in creating a healthier, greener city, which led to the creation of the Green City Plan.

Empowering communities is a priority under the Air Quality Action Plan, with 3 behavioural change projects being taken forward alongside other actions, including new actions to tackle particulate pollution and carbon dioxide emissions from wood burning stoves.

- Woodburning: Southampton is partnering with local charity The Environment Centre to use data from a series of 18 air quality monitors as a means to promote awareness and a shift away from woodburning, counteracting misconceptions about it being a green heating source and raising awareness about the health impacts. The logic is that having accurate information will be a driver for change in behaviour, as will the positive health benefits.

- Schools: with 9 monitors located in schools, a series of lessons and fieldwork will enable children to participate in citizen science experiments. Engaging pupils is all about encouraging them to walk to school via safer side roads and parks, not on main roads, to reduce their exposure to air pollution in the short term while the city works towards lower pollution in the long term.

- Healthcare: GPs, consultants and other healthcare workers aren’t given training on air quality in medical school, yet they’re powerful allies in advising patients to change their behaviours in order to reduce their vulnerability to air pollution. This pressing gap prompted Southampton to design an engagement project with local hospitals, with the aim of transforming these professionals into Clean Air Champions. Southampton has benefited from the wide range of clean air resources produced by Global Action Plan.

“To date, air quality monitoring broadly focuses on monitoring NO2 at roadside locations. We recognised that the woodburning engagement project would really benefit from an enhanced network of monitors which captures particulate matter fractions in more residential areas.”

George O’Ferrall, Air Quality Lead, Southampton City Council

Tackling inequalities

The schools and healthcare engagement projects will incorporate air quality and deprivation data to understand where poor air quality has the greatest impact on public health and target action there. A commitment under the updated Air Quality Action Plan is to carry out a more detailed mapping exercise to better understand local health inequalities in the city and how they interact with air quality.

Joined-up action

The public consultation was clear that stakeholders and residents wanted to see wider changes implemented, including better public transport and active travel measures, which are now incorporated into the Green City Plan. The council is now committed to updating the Air Quality Action Plan to align with the objectives of the Green City Charter.

In addition to measures on public transport and active travel, the council is assessing the viability of larger, strategic opportunities such as workplace parking levies, emissions-based parking charges, localised road closures and green shipping tariffs. As a unitary authority and therefore the local transport authority, council air quality officers work closely with transport teams to ensure that actions to improve the local transport network also consider improvements in air quality.

Active Travel Zones are now a key part of the Local Transport Plan, and the council is continuing to develop initiatives as part of the Transforming Cities Fund and Active Travel Fund programmes. Highlights in 2022/23 included:

- Ongoing development of two Active Travel Zones in Portswood and Woolston, as well as new pedestrian crossings, segregated cycle lanes and new pedestrianised areas in other locations.

- 13 permanent and 6 temporary School Streets across the city.

- Phased roll-out of 20 mph streets across the city.

- A cycle hire scheme operated by Beryl Bikes, launched in October 2022, and recently expanded to include additional docks and bikes.

Plans for 2023/24 include a Safer Routes to School programme.

Working across departments

Proving the positive impact of breaking out of silos, the award-winning Air Quality Action Plan was developed with the input of council officers across a wide range of departments: Environmental Health, Planning, Transport Policy, Economic Development, Sustainable Transport, Green City and Public Health.

What resources were needed?

Southampton City Council applied for funding from DEFRA’s Clean Air Fund and was awarded £1,807,303 to introduce the CAZ. This fund, as well as finance from the government’s Clean Air Zone Implementation Fund, covered the key transport measures that were taken in the plan.

Approximately £950,000 of DEFRA air quality funding has been secured over the past 4 years to deliver the programme of behavioural change projects, in line with DEFRA’s requirements for projects to help improve awareness of air quality and reduce exposure to pollution, as well as reduce particulate matter emissions.

Many of the sustainable travel measures crucial to improving air quality are being funded by the Transforming Cities Fund. Southampton City Council and Hampshire County Council were awarded £57 million of government funding, with additional funding coming from local contributions with the council and its partners.

Southampton has a dedicated air quality team, including an officer role created specifically to engage with schools that'll now have a broader remit to deliver engagement in other areas.

However, as air quality improves, Southampton may find it harder to secure funding for its air quality team and other measures. Grants are competitive and more likely to be awarded to areas with the poorest air quality. While some degree of prioritisation makes sense, it’s important that councils have the long-term resources they need to create genuinely healthy local environments with joined-up solutions, not just a short-term emergency approach. This is especially important given that the WHO introduced new guidelines for air pollution in 2021, based on evidence of health impacts, which are much lower than the current UK legal limits (10 micrograms per cubic meter rather than the UK's 40).

Lessons from Southampton

Engaging with taxi drivers

It was essential to engage with taxi drivers who had concerns about the financial impacts of the CAZ. As a result, they loudly opposed charging schemes as well as non-charging schemes that don't offer the right support. A key learning point was the need to carry out extra engagement and encouragement with taxi drivers. The council noticed that, as this sector is very well networked, once significant engagement had allowed for a small number of drivers to switch to low-emission vehicles, these drivers shared their experiences with their peers. This allowed support to quickly build among the sector’s workers.

This lesson helped inform the engagement approach for the council’s newer electric vehicle "try before you buy" scheme. Officers engaged with the trade as soon as possible and used early adopters of the scheme as case studies for other drivers.

Responding to unexpected challenges

Southampton was on track for all buses to be compliant with the Euro 6 standard until operator First Bus took the decision to leave the city. Bluestar became the sole operator in Southampton leaving numerous routes underserviced, so Bluestar had to draft in other buses from across the country to ensure the public transport service wasn’t impacted. Some of these buses weren't compliant with Euro 6. Bluestar is working to bring in newer buses as soon as practicable. The council will require it to do so by spring 2024 as part of an Enhanced Bus Partnership agreement and the Bus Service Improvement Plan, which'll require all buses to be compliant with Euro 6.

Working with the Port of Southampton

Southampton City Council has worked with the Port of Southampton, a major economic and transport hub, and a contributor of pollution in the city, both from the cruise ships and the traffic that the port generates. ABP Southampton, which manages the port, is now working on the challenge of managing air quality in and around the port, including:

- Investment to transition over half the port’s fleet to electric.

- Introducing cycle infrastructure on its site.

- Installing the UK’s first shore power facility for cruise ships powered by renewably generated energy, so that ships that use this berth will be zero emissions when they “plug in”.

- In the same year, Southampton’s port reached the milestone of 50% of power generated from solar. Overall, the port has reduced its energy consumption by 40% since 2009, despite doubling its activity over the same time period.

Some of these actions have been inspired by the ongoing dialogue with the council. For example, shore power was originally considered under the NO2 plan but was unable to be funded at that time. ABP went ahead on its own initiative to implement this with funding from the Local Enterprise Partnership in 2022.

“As a major employer and responsible neighbour, we are proud of the role we and the wider port community have played in accelerating air quality improvements in Southampton. We will continue to implement initiatives and share our experiences with others to ensure these improvements continue.”

Alastair Welch, Director of ABP Southampton

Co-ordination with national government

Working with DEFRA and the Joint Air Quality Unit (JAQU) was necessary and sometimes challenging, including:

- Several court iterations in order to gain legal compliance and approval of the Local NO2 Plan.

- Developing the business case report for bringing air quality to legal levels.

- Putting the initial measures of the Local NO2 Plan in place.

For example, introducing measures to ensure buses and private hire vehicles moved to lower-emitting alternatives needed multiple iterations and amendments from the government, taking almost a year to be approved. A key lesson learned was to carry out extra in-depth consultations with stakeholders to be better aware of issues that'll arise months or years in the future.

However, now Southampton’s Local NO2 plan has government approval, a model exists for other local authorities to go through a similar process. This means that another council replicating this work will be able to save significant amounts of time.

Useful information

Related projects

We've found some examples of other council activity on this topic.

- Birmingham City Council is improving air quality with its CAZ, which charges the most polluting vehicles.

Friends of the Earth's view

Southampton City Council’s approach to cutting pollution without charging drivers is an interesting one. So far the council has succeeded in meeting current UK legal standards, which is encouraging, but as with any traffic pollution measures introduced in the last couple of years, the impact is still hard to fully assess due to changing travel patterns during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The council needs to remain fully committed to improving air quality and should now aim to meet the new WHO guidance levels for NO2, which are based on up-to-date evidence of health risks. Councils need to be supported by national government to meet WHO guidelines. The council may need to reconsider charging if further pollution cuts aren't delivered.

What's encouraging is the level of public backing the council had, not only for tackling pollution from cars but also for linking health and environment in other ways, which has prompted the council to go ahead with wider measures to improve walking and cycling, and boost nature in the city. Local community groups will be looking for good progress on these measures.

Councils should consider multiple ways to cut car use, including re-allocating road space (Action 23 of the Climate Action Plan) and ensuring new development isn't car-dependent (Action 28). Otherwise traffic levels and pollution could rise again with new car journeys related to new housing.

Friends of the Earth is showcasing specific examples of good practice in tackling climate change, but that doesn’t mean we endorse everything that a council is doing.

This case study was produced by Ashden and Friends of the Earth. It was originally published in March 2022 and was last updated in September 2023. Any references to national policy in this case study relate to policy under the previous government and reflect the policy context in which the council was operating at the time.